She lies fasting, giving her body up to pain, wasting away in tears all the time ever since she learned that she was wronged by her husband.

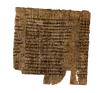

Euripides, Medea, 24-25, trans. David Kovacs, in: Cyclops. Alcetis. Medea, Euripides Volume I, Loeb Classical Library 12, ed. David Kovacs, Cambridge MA, 1994.

Medea’s Pain

Euripides, Medea

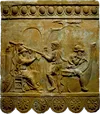

Medea, the beautiful princess of the faraway land of Colchis, is devastated by loss – her lover, the hero Jason, has abandoned her. The horror of her revenge can scarcely be imagined: seeking retribution, she will stop at nothing – and will ultimately even murder her own children.

Fearsome sorceress, crazed lover, powerful woman constrained by society: Medea has many faces, and remains one of the most compelling female figures in Greek mythology.

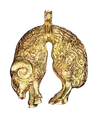

The exhibition “Medea's Love” at the Liebieghaus tells the myth of Medea and Jason: The story of a disastrous love affair, full of adventure, heroes, and traitors. Celebrated antique works bring the story to life, from the perilous expedition of Jason and the Argonauts and the quest for the Golden Fleece to the lovers’ murderous deeds. Gold objects and items of jewellery that have survived millennia and originate from Medea’s home in modern-day Georgia provide an impressive backdrop to the ancient tale.